DAIFUKU SolutionsSmart Production of Dry Cell Batteries with Overhead Transport Systems and Automated Storage and Retrieval Systems

Panasonic Energy Co., Ltd., which produces everything from dry cell batteries to industrial and automotive batteries, relocated its dry cell battery production facilities to the Nishikinohama Factory in Kaizuka City, Osaka. In conjunction with this move, Panasonic Energy also introduced an automated solution consisting of overhead transport systems and automated storage and retrieval systems (AS/RSs). Toma Suzuki (left in photo), Senior Manager of Production Engineering Department in the Energy Device Business Division, and Mamoru Kuwahara (right) of Daifuku’s Automotive Division, who oversaw the project, introduce the Panasonic Energy’s first significant automation initiative and factory relocation project which lasted about three years from 2021 to 2023.

Can you give us an overview of the Nishikinohama Factory and the reasons behind relocating dry cell battery production there?

Suzuki: The Nishikinohama Factory is Panasonic Energy’s only dry cell battery production site in Japan and one of the largest in the country. The site produces dry cell batteries ranging from D to AAA, primarily serving domestic demand. The factory was previously a solar cell module production site, but we completely renovated the facilities and started full-scale operations in 2023, marking the 100th anniversary of our energy-related business.

The Moriguchi Factory, located in Moriguchi City, Osaka, served as our main battery production site for over 90 years. However, due to issues such as aging buildings, we undertook the project of transferring dry cell battery production to the Nishikinohama Factory, which I joined as a production facility designer. Our concept was to establish a global flagship factory for the future of the dry cell battery business and to fulfill our responsibility for future market supply. We set out to build a smart production system suitable as a global flagship for dry cell battery production.

Optimizing inventory and improving production planning accuracy

When installing the equipment at the Nishikinohama Factory, what aspects did you focus most on?

Suzuki: At the Moriguchi Factory, we were producing up to 48 million D to AAA dry cell batteries per month. Our goal was to maintain this production capacity while also addressing various production challenges.

One of those challenges was inventory management. Traditionally, dry cell batteries were stored in shrink-wrapped packs of multiple batteries. This meant that if we ran out of for example two-pack stock, we couldn’t repack ten-pack stock for shipment. Instead, we would have to produce new batteries. So, by storing batteries unpackaged, we could make it easier to respond to fluctuations in demand, improve the accuracy of production planning, and reduce the total amount of inventory. This is one example of how we revised our system.

Improving our workflow was also essential. All processes at the Moriguchi Factory were handled in a single building, and we used carts and other vehicles to transport material between processes. However, with 20% more floor space at the Nishikinohama Factory, the factory was essentially split into three, with materials, works in process, and finished products flowing from Building A downstream to Building C. With greater distances between processes, we calculated that we would need to significantly increase our staff to continue transporting products manually. Given how difficult it would have been to secure more staff, and due to concerns about the risk of dry cell batteries falling or tipping over during transport, automation became a necessity.

Would manually transporting with carts have posed a significant burden for staff?

Suzuki: Even small batteries are dense, and when packed in boxes, they become quite heavy and difficult to handle. Plus, stacked boxes are at risk of tipping over, resulting in high safety and quality risks, so we had to look for a safer, more efficient way to transport products. Even though we have a wide variety of facilities designed in-house, we decided that it would be better to seek the help of outside experts for storage and transport automation.

Drastic improvements to inventory management and efficiency by combining overhead transport systems and AS/RSs

Is that how Daifuku became involved in the project?

Suzuki: Yes, exactly. We approached several companies for ways to automatically sort the various-sized cases handled during production, but no one was able to come up with what we needed. Daifuku provided us with comparative data and proposals to make such a system feasible, which we greatly appreciated. Although we initially planned to use conveyors for transport, fitting the conveyors to the layout was too much of a challenge. Daifuku’s prompt responses to our inquiries led to a smooth decision to officially work with them.

Kuwahara: In the fall of 2021, we received an inquiry about our SPDR (Spider) temporary storage and sortation system. At the Moriguchi Factory, boxes of batteries were being stacked flat, and employees followed shipping slips for manual storage and retrieval. The original request was to automate this workflow, but we thought it necessary to address a wider range of issues. After consideration, we determined that our Mini Load AS/RS was more suitable because it could handle the different case sizes for D batteries to AAA batteries, and it allowed us to reduce the storage space to one-third of that required for flat storage.

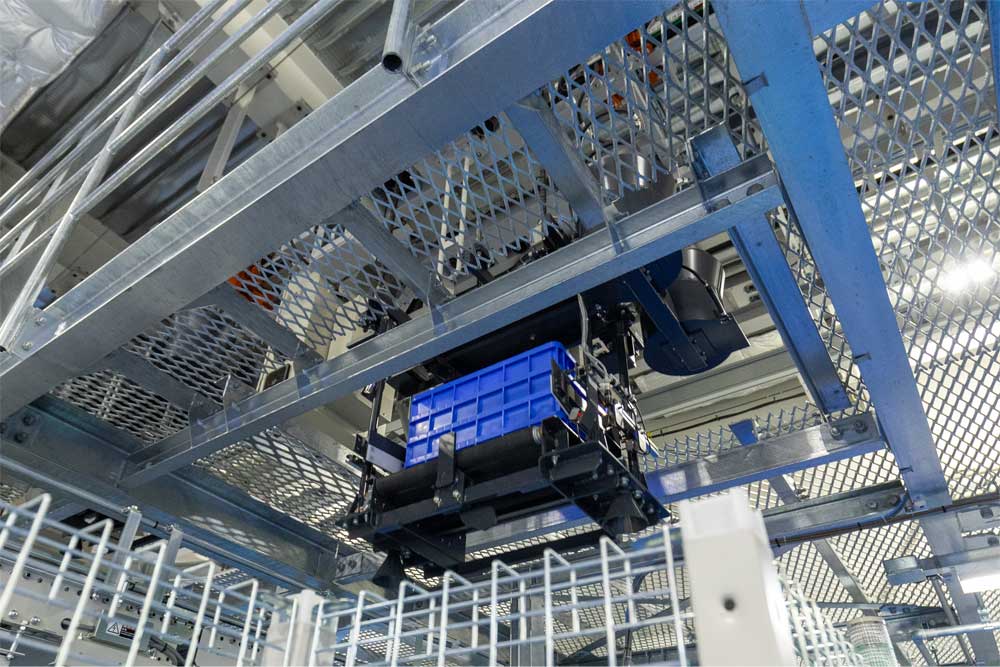

For transporting products, we proposed the Ramrun monorail transport system to make effective use of the building’s overhead space. The workflow we devised involves transporting completed batteries from Building B to the automated warehouse in Building C by conveyor, and using the Ramrun system for transporting products to the packaging processes and for returning empty boxes after transport.

Typically, load capacity can be a big concern with overhead transport, but Daifuku’s Ramrun system is also used by automotive manufacturers for transporting vehicle bodies and other heavy parts, and it can be easily customized to meet a variety of needs, including carrying objects ranging from lightweight pieces to those weighing several tons. At the Nishikinohama Factory, the maximum transport weight is about 80 kg for D batteries, which the system could handle without any problem. This project also included a barcode system for changing position and speed commands with Ramrun, ensuring easy adaptation to future changes in the production plan or for relocating or expanding the Ramrun stations.

Automated overhead monorail system for transporting containers

Storing inventory in an AS/RS via conveyor

Transport containers loaded with dry cell batteries

Was this the first time you introduced AS/RSs or automated transport systems?

Suzuki: This was our first time introducing an automated system on such a large scale, and while the preparation was somewhat challenging, the elimination of the need to secure additional staff was a major benefit. Also, at the Moriguchi Factory, we had to visually search for products on pallets lined up on the floor. The new tracking system now allows us to quickly locate specific products, significantly improving operational efficiency.

Optimizing automation and mechanization while deciding which tasks to perform manually

How did your employees respond to the changes in operations and workflows?

Suzuki: At first, not all employees were in favor of the changes, partly because the workers on the floor were accustomed to the conventional production system. To address any concerns, we shared information from the design stage, visualizing and communicating issues such as the Nishikinohama Factory’s increased transport distances. We also visited the facilities together to show what kinds of automation equipment were available. Many worried that the total inventory would decrease after the introduction of an AS/RS, so we ran simulations based on production results over the past three years. This allowed us to demonstrate that there would be no problem with reduced inventory. We focused on visualizing and quantifying information to alleviate uncertainty about what the changes would bring.

What challenges did you face during the relocation process?

Suzuki: Relocating the factory was quite smooth. At the Nishikinohama Factory, we produce D and C batteries on the first floor and AA and AAA batteries on the second, with similar equipment on both floors. To ensure dry cell battery production would not be interrupted during the relocation, we focused on the production of D and C batteries at the Moriguchi Factory, and once sufficient inventory was built up, the production facilities were dismantled and reassembled at the Nishikinohama Factory. We then did the same for AA and AAA batteries, completing the relocation in stages.

However, we did have some unexpected issues arise when installing the equipment. The Nishikinohama Factory was a solar cell module production site up until 2003, and although we laid out our equipment based on the original design drawings, we found unmarked electrical facilities and piping. We also discovered that the roof slopes gently, resulting in a varying ceiling height on the second floor. However, Daifuku thought of ways to flexibly accommodate for these unforeseen problems, such as by extending the overhead transport system.

Kuwahara: Despite having to secure materials and arrange work to extend the rails unexpectedly, with the cooperation of everyone on-site, we completed the installation without any major issues, which was a relief.

As a factory dedicated to the future of dry cell batteries, do you have any other automation plans for the future?

Suzuki: We have automated the process up to just before shrink-wrapping, but we are also considering improvements in subsequent processes. Currently, we have to manually load cardboard boxes of products weighing 15 kg or more on to pallets, which we then load onto trucks with forklifts. We have to lift and unload these boxes more than 1,000 times every day, so we would like to automate this process.

Overall, we have automated about 80% of the operations at the Nishikinohama Factory. The remaining 20% mostly involves supplying positive and negative electrode materials, and while there is still room for automation, we don’t plan to automate all operations at the factory. There are still some situations that require human intervention, such as with temporary machine stops. To respond appropriately to such situations, we first have to secure a safe work environment. Keeping production going in the event of a problem also requires a certain familiarity with the site, and this also requires human involvement. Going forward, we will continue to think about how best to have our workers and machines work together.

Since launching operations in 1966, we have also focused on community engagement, with more than one million people having participated in factory tours and battery-making workshops. We have also revamped these programs to offer even more enriching experiences. Going forward, we plan to continue to share our factory with the public to become a more community-oriented facility than ever before.

Toma Suzuki

Production Engineering Dept., Manufacturing Management, Consumer Energy Business Unit

Energy Device Business Division

Panasonic Energy Co., Ltd.

Toma Suzuki joined Panasonic Energy in 2016. He was involved in the maintenance, design, and development of production equipment at the Moriguchi Factory, which focused on dry cell battery production. In 2020, he transferred to the Global Manufacturing Promotion Department, where he worked on introducing new equipment at overseas production sites, including in Thailand. He has been in his current position since 2022 and remains dedicated to building manufacturing systems that will shape the future of the dry cell battery business.